-

Full Press - Click Here

-

Selected Press:

- Reviews

- DVD Reviews

- Feature Articles

- Interviews

- Photo Scrapbook - Coming Soon

- Links of Note

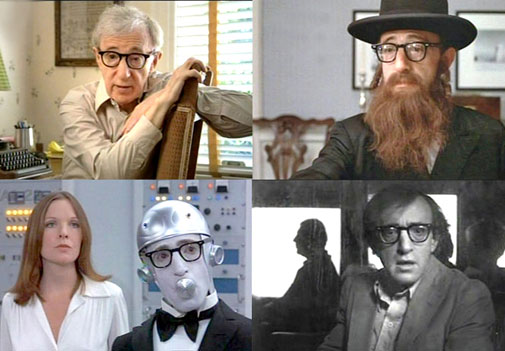

The Many Faces of Woody Allen

By By Eric Gould

© Tvworthwatching, November 18th, 2011 permalink

Coming up on PBS Sunday and Monday at 9 p.m. ET, Nov. 20-21 (check local listings), are four hours of actors, writers and critics lining up to pay homage to one of the true auteurs of our time -- one who somehow was able to muse on life's great metaphysical mysteries while slipping on a giant banana peel, or dressed as a Hassidic Rabbi.

As shown in this new American Masters retrospective, Woody Allen: A Documentary, he often did it in the persona of his own doppelganger -- a nebbishy intellectual who could capsulize the human comedy, and win the affections of leading ladies, all in couple of quips...

Now 76, Allen has given us an amazing 50-year-plus career of short stories, New Yorker articles, stand-up routines, TV appearances and films. And he's still going. He roared back this year with the international success of the remarkable Midnight in Paris.

And in the middle of it all, he married a girl who was, ostensibly, his step-daughter.

With Woody -- to those who know him well, including Diane Keaton, Dick Cavett, Sean Penn, and Larry David -- it's all about the work. And that's what they're there, along with Allen himself, to discuss. The origins and scope of it. The depth of it. The brilliance of it.

And in so many fascinating ways, that's what the documentary should be taken as: the definitive survey of a brilliant body of work.

Woody Allen: A Documentary is four hours in two parts. It was made when Allen finally relented, after numerous requests, and gave filmmaker Robert Weide six interviews, access to his Manhattan apartment, and allowed himself to be filmed on set directing.

Perhaps the most surprising thing we learn, and early on, is that it all came so easily and naturally for Allen from the beginning. He was, essentially, a teenage prodigy, a paid joke-writer for New York columnists while still in high school.

He was that smart, that good. In a CBC interview from 1967 he says, "I'm always amazed when somebody can draw a horse. I can't figure out how they could possibly do it... and I can't draw a horse, or anything else.

"But I can write jokes. And it's hard not to write them. If I walk down the street -- it's like it's my normal conversation. It just comes out that way."

And then, one after another, come the career achievements. Wresting total creative control for his second film, Take the Money and Run, in 1969, and never relinquishing it again. Getting four Oscars for Annie Hall in 1977. A Best Picture Oscar for Manhattan in 1979. All seem to fall in line, like brilliant plot points of one of his well-crafted scripts.

Perhaps most revealing, and somehow expected, is how Allen as an artist is in constant struggle with the success and peril of his work.

Right at the start ofn the documentary, he sums up the futility and absurdity of trying to make a great film, which he feels he never has.

"Writing," he says, "is the great life, because you wake up in the morning and you write it and you imagine it's Citizen Kane... But when you have to then take it out and do it, then reality sets in. Then all your schemes about making a masterpiece are reduced to: 'I'll prostitute myself any way I have to survive this catastrophe.'"

And the documentary goes on, in some detail, to flesh out the impassioned risks and mishaps of a great writer tearing up hard-won pages, cutting out chunks of scenes in the editing room, and interviewing actors during casting meetings, never letting the conversation go to himself as a subject.

There are wonderful insider moments on his habit to take clutches of scribbles and notes and churn them into brilliant pages of dialogue, as he's done for a half-century on the same old Olympia typewriter.

And more. But there is always the scandal.

To Weide's and Allen's credit, they do address his spilt with Farrow, and the ensuing marriage to Soon-Yi Previn, albeit slantingly and indirectly. Unfortunately for us, for Allen, and for his friends and colleagues, what is referred to in the documentary as the "upset with Mia" is something that will always be just underneath the surface of his legacy, and remains in this documentary.

If Weide prefers to side-step here, in practicality, how could he not? As the documentary unfolds, the subjects of Allen's writing and interests are so complex and intertwined, you realize that the upturning of his life for a tabloid scandal cannot have a simple explanation or understanding. Nor should Weide and the actors be put in the role of apologists.

So it's left only to ponder the relationship for what it was and how it came to be: bohemian, immoral, deviant, ironic Greek tragedy, Freudian mess, or whatever else best seems to characterize it.

It's the best that can be done. Especially if you're still a fan of the work. And Allen himself might have us look to it and perhaps form answers, and meanings, of our own.

Woody Allen: A Documentary includes wonderful clips from Annie Hall and Manhattan, milestone films in which he began to fuse his slapstick wit with deeper, adult themes of love, death, anxiety and existence.

These would go on to form the future underpinnings for dozens more. We revisit the more oddball but more direct variations, such as his homage to Italian director Federico Fellini in Stardust Memories. And, always, there are the unforgettable, often revealing one-liners.

As his neurotic character Alvy Singer says to Keaton in Annie Hall, "I feel that life is divided up into the horrible and miserable... The horrible would be like terminal cases, the blind, the cripple. I don't know how they get through life. It's amazing to me.

"And the miserable is everyone else. So when you go through life, you should be thankful that you're miserable. Because you're very lucky to be miserable."

Perhaps most ironic about Allen's near professional self-destruction in 1992 was that he had almost completed Husbands and Wives, an uncanny, eerily timed peek into his personal life just as it exploded. It is just given just a few moments in the documentary, but it serves to remember Sydney Pollack's character of Jack, who, lamenting his midlife foolishness for leaving his wife for an aerobics instructor, rues how "the heart wants what the heart wants."

The line isn't directly quoted, but, it certainly foretells a certain philosophical surrendering of reason, and an almost simultaneous dread of the consequences. And it all came to be too painfully true to life.

While we assume Husbands and Wives was ripped from the personal pages of his life, Crimes and Misdemeanors is another opportunity in the interviews for Allen to issue his ongoing denial: namely, that he is not the same as the characters he plays, while we usually, reflexively, presume the opposite.

Weide is clever enough to give time to 1997's Deconstructing Harry, about a writer inventing a character for a novel. All the while, Allen's doppelganger Harry argues that his fictional subject, whom the public suspects is really Harry himself, has nothing to do with him at all. It's a meta-Russian Doll routine, the fictional equivalent of Allen's factual argument.

Except, in the film, the audience is the rube. Allen, portraying Harry, is asked about his relationship to the fictional alter-ego characters he creates. "It's me," he admits to an interviewer, "thinly disguised as the character. In fact, I don't even think I should disguise it any more. It's me."

It's an inventive double-switch, a meta-confession by a clone -- and an assertion that keeps his audience guessing, and frees him to explore himself directly in film, or not, without ever having to admit it, or directly discuss it.

It's a shell game to make any literary recluse proud.

In this American Masters two-parter, Allen discusses these and other public assumptions about him with a lack of affectation and casualness, as if listing the ingredients of barley soup. This passivity and intellectual happenstance is as much his trademark as his rumpled corduroys, and it serves him well.

As such, he's detached. He's well known for the wide berth he gives to his actors, preferring them to draw upon the talent that got them into his films in the first place, rather than maneuver a performance out of them.

Sean Penn pinpoints it best when he says, "HIs feeling is that the best, complete thing he is going to get is going to come out of the actor's instinct... When it comes to directing an actor he has a bare-bones clarity that any personality can understand and interpret."

And you can see the triumph of this method over and over again, in clips from Mighty Aphrodite, Purple Rose of Cairo, and many others.

Allen's closing words are very funny musings -- that, while achieving great things in life, he still has the vague, free-floating anxiety that he still got screwed somehow. The joke is utterly consistent with his life-long celluloid psychoanalysis.

But maybe a less flippant closing, one made soberly and with heart, would have been a better ending -- and Allen already has filmed it. It's the closing monologue from 1989's Crimes and Misdemeanors, which telegraphed what was to come for him, as well as the metaphysical territory he now occupies.

The sentiment can be found, and heard, on YouTube, in the clip HERE. But in what it says, and how it says it, the words written by Woody Allen deserve to be quoted verbatim in print, and pondered seriously:

"...We define ourselves by the choices we have made. We are, in fact, the sum total of our choices. Events unfold so unpredictably, so unfairly, human happiness does not seem to have been included in the design of creation.

"It is only we, with our capacity to love, that give meaning to the indifferent universe. And yet, most human beings seem to have the ability to keep trying, and even to find joy from simple things -- like their family, their work, and from the hope that future generations might understand more."