-

Full Press - Click Here

-

Selected Press:

- Reviews

- DVD Reviews

- Feature Articles

- Interviews

- Photo Scrapbook - Coming Soon

- Links of Note

Funnyman who’s serious about work

Film traces Allen’s career from gag writer to character-driven director

By Saul Austerlitz

© The Boston Globe, November 20th, 2011 permalink

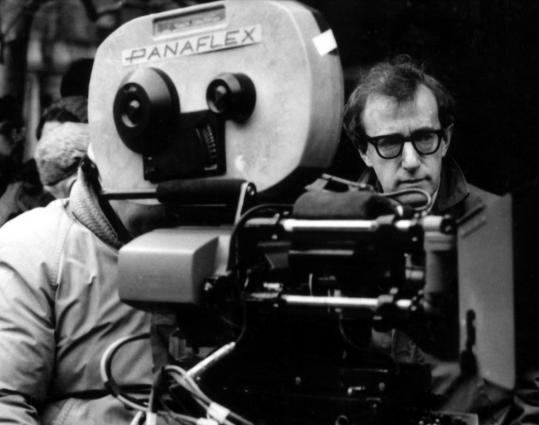

(Brian Hamill/MGM)

(Brian Hamill/MGM)

Woody Allen in the “American Masters’’ documentary about his life and career. “I put a higher value on the tragic muse than the comic muse,’’ he says in the film, part 1 of which airs tonight.

Back when Woody Allen was a teenager in Midwood, Brooklyn, named Allen Konigsberg, he used to crank out dozens of jokes a day for a press agent looking to get his clients’ names in the newspapers. Comedy has always come easily for him - so easily, in fact, that Allen appears to value his work only insomuch as it eschews punch lines in favor of deeper, darker musings. “There’s no question that comedy is harder to do than serious stuff,’’ Allen told Eric Lax in his 2007 interview book “Conversations With Woody Allen.’’ “There’s also no question in my mind that comedy is less valuable than serious stuff.’’

As if we hadn’t already known it, PBS’s “American Masters’’ comes along to confirm that, indeed, Woody Allen is a great American filmmaker, and something of a national treasure, albeit a deeply flawed one. Broadcast over two nights beginning today, “American Masters - Woody Allen: A Documentary’’ is a brisk trot through a career that spans more than 50 years, including Allen’s more than 40 films as a director. Directed by Robert Weide, the documentary offers a tantalizing array of little-seen footage - you haven’t really lived until you’ve seen Allen boxing a kangaroo, or serenading a talking dog - interviewees reflecting on Allen’s career, and well-chosen clips from his work.

For all Allen’s many talents as a writer, director, and performer, his abilities as an assessor of his own work have always been dubious. In interviews dating back to the 1970s, and in his comments in this film, Allen makes his own attitude toward the hierarchy of his work abundantly clear. Having begun as a punch-line-spouting comic wunderkind, Allen believes that his work grew stronger and more serious with the Oscar-winning “Annie Hall’’ (1977), which mingled his traditional comic sensibility with the powerful relationship between Allen’s Alvy Singer and Diane Keaton’s Annie. Allen’s career, in this point of view, progressed through the dramatic-comedic counterpoint of “Hannah and Her Sisters’’ (1986) and “Crimes and Misdemeanors’’ (1989), and culminated in his wholly non-comedic 2005 film “Match Point.’’

“One could say they were essentially trivial,’’ he says in the documentary of his early films, “and be right.’’ Allen has written off early comic masterworks such as “Take the Money and Run’’ (1969) and “Sleeper’’ (1973) as juvenilia, eventually clearing the way for more mature efforts. Allen is not wrong to note the change in his work; where early films were composed of broad comic bits and abundant one-liners, it was not until “Annie Hall’’ and after that he introduced genuine characters - and genuine emotion - into his oeuvre. But just because “Bananas’’ (1971) lacks the sophisticated veneer of “Manhattan’’ (1979) does not make it inferior. And even in Allen’s post-“Annie Hall’’ period - a period, it hardly needs pointing out, that has now lasted some 35 years - much of his best work, such as “Broadway Danny Rose’’ (1984), “The Purple Rose of Cairo’’ (1985), and “Deconstructing Harry’’ (1997), has melded nuanced character study with broad, slapstick humor.

In interviews, Allen has made clear that he views his career, in large part, as an effort to scrub his films clean of their comic tarnish. “Crimes and Misdemeanors,’’ he muses, might have been better had it focused solely on Martin Landau’s crimes, and not Allen’s own character’s misdemeanors. “I don’t want to make funny movies anymore,’’ Allen’s character moans in 1980’s “Stardust Memories’’ (a moment shown in “American Masters’’). “They can’t force me to.’’ In this telling of Allen’s career, which the director has collaborated in offering to journalists, and now to Weide, “Match Point’’ is the film he is proudest of, precisely for the complete absence of humor. “I’ll sacrifice some of the laughs for a story about human beings,’’ Allen tells Weide, describing his mindset, “and it will be richer.’’

“I put a higher value on the tragic muse than the comic muse,’’ Allen says in the film. “I’ve always felt that tragic writing, tragic theater, tragic film, confronts reality head-on, and doesn’t satirize it, tease it, kid it, deflect it, opt out with some kind of a gag at the last minute. It’s harder for me, I embarrass myself more readily, but I get more pleasure out of failing in a project that I am enthused over than in succeeding in a project that I know I can do well.’’ Allen is well aware of his own lavish comic gifts, and undervalues them as a result of the ease with which he can access them.

Allen’s feelings are reflective of the general second-class status of comedy, perpetually the ugly duck of American film. Comedy grabs few Oscars, and takes few critics’ prizes; all it generally wins is the devotion of its fans, and the laughs of its audiences. American comedy is the province of Chaplin and Keaton, of W.C. Fields and Mae West, of Jerry Lewis, and yes, Woody Allen. Comedy suffers from a lack of respect, and it surely does not help matters that one of its most brilliant practitioners sees it as a dim-bulb nephew to suave, sophisticated drama.

Allen is, of course, permitted to believe whatever he likes about his own work. But we, as viewers, should not confuse the director’s perspective on his career with reality. Allen is, as he always has been, a comic filmmaker. This is not a criticism, whatever Allen might think of it. Comedy is Allen’s lifeblood, from his days as a youthful performer in the Catskills to the present, and it is the backbone of his work as a filmmaker. Picturing his premature death, Allen cracks that “the world would be poorer a number of great one-liners.’’ He says that like it’s a bad thing. Whatever he may tell us about the relation of drama to comedy in his own mind, his films say something else. Allen’s character in “Stardust Memories’’ encounters an alien spaceship, and asks them for guidance as to how to live a better life. “You want to do mankind a service?’’ the alien, who sounds suspiciously like the director himself, asks him. “Tell funnier jokes.’’